.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

Having gone to Ouray and Silverton, visited Orvis Hot Springs and done a little off-roading, crossed both Molas and Red Mountain Pass (only open weekends and from noon to 1:00 p.m. on weekdays as crews push to complete work before the snow flies) today we'll drive even further into southwestern Colorado near the Four Corners region, and spend the day visiting Mesa Verde National Park.

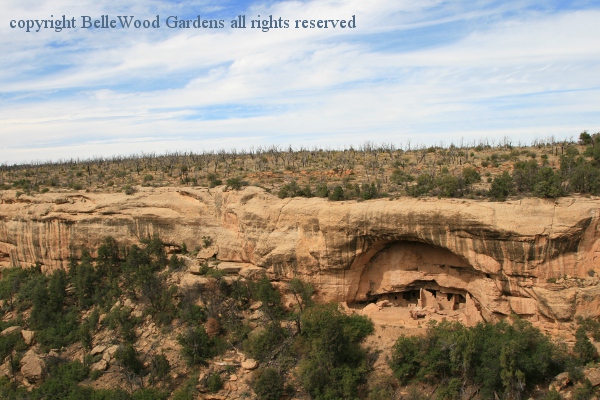

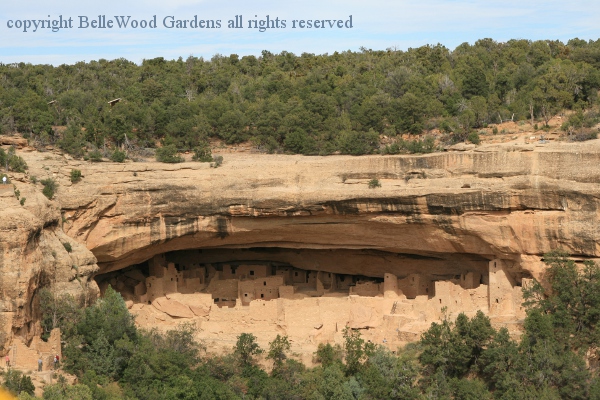

Created by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, located about 35 miles west of Durango between the towns of Mancos and Cortez, the Mesa Verde national park entrance is along Highway 160. Once we enter the park we still need to keep driving. At 52,485 acres, the first view of a cliff dwelling is 21 miles in, along a steep, narrow, and winding road. A U.S. National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site, it protects nearly 5,000 known archeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings. These are some of the best preserved Ancestral Puebloan archeological sites, some of the most notable and best preserved in the United States. The ancient Puebloans survived using a combination of hunting, gathering, and subsistence farming of crops such as corn, beans, and squash. They built the mesa's first pueblos sometime after 650, and by the end of the 12th century they began to construct the massive cliff dwellings for which the park is best known.

Sit back. Relax. I have a story to tell you. Like all good stories this one begins once upon a time. So. Once upon a time, a very, very long time ago, about 7,500 years BCE, the region we now call Mesa Verde was seasonally inhabited by a group of nomadic Paleo-Indians known as the Foothills Mountain Complex. Leap forward a few thousand years and the Archaic people established semi-permanent rock shelters in and around the mesa. By 1,000 CE, the Basket Maker culture emerged from the local Archaic population. And by 750 CE the ancestral Puebloans had developed from the Basket Maker culture.

Mesa Verde, Spanish for green table, offers a spectacular look into the lives of the ancestral Puebloan people who made it their home for over 700 years, It was different long, long ago, it was greener back then. And then the climate changed. Sound familiar? Driven by environmental instability - a series of severe and prolonged droughts - by 1285 CE, the ancestral Puebloans abandoned the area and moved south to locations in Arizona and New Mexico. Descendants of Mesa Verde ancestral Puebloans include the Hopi in Arizona, and the multiple Rio Grande pueblos of New Mexico.

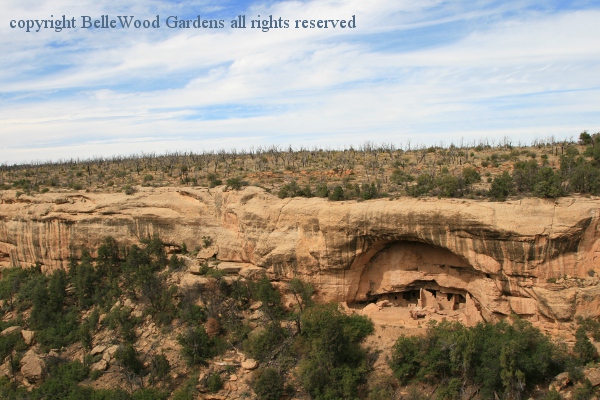

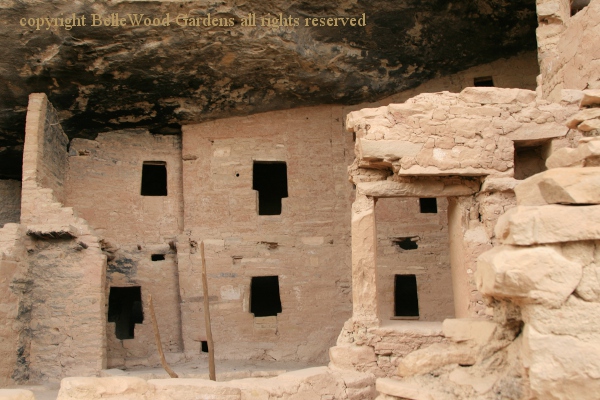

A better look at Oak Tree House, previously seen from across the canyon.

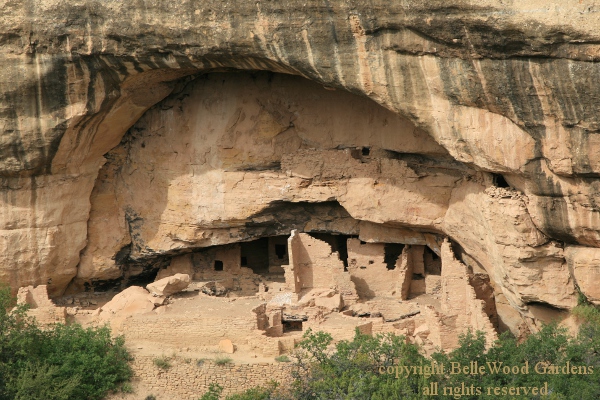

The cliff dwellings were built to take advantage of solar energy. The angle of the sun in winter warmed the masonry of the cliff dwellings, warm breezes blew from the valley, and the air was ten to twenty degrees warmer in the canyon alcoves than on the top of the mesa. In the summer, with the sun high overhead, much of the village was protected from direct sunlight in the high cliff dwellings. At 7,000 feet the middle mesa areas were typically ten degrees cooler than the mesa top, which reduced the amount of water needed for farming. The climate is semi-arid. Water for farming, cooking, and drinking was provided by summer rains, winter snowfall, and seeps and springs in and near the Mesa Verde villages.

We walk down to Spruce Tree House, with 130 rooms and eight kivas making it the third-largest village. Built sometime between 1211 and 1278 CE, it is thought to have been home for 19 households with anywhere from 60 to 80 people at one time. As real estate agents are fond of saying, it's all about "Location, location, location!" And Spruce Tree House was located within several hundred feet of a spring.

Not windows, these are two types of doorways. The more-or-less rectangular openings probably lead to family living quarters. There are two explanations for the T-shaped doorways: perhaps practical, for someone carrying a large load. Or maybe they lead into areas shared by more than just one family. Or, into a space where religious observances were held.

We climbed down this ladder into one of the kivas. A modern replica, even so the rungs are dished by the feet of people climbing up and down. Buried chambers have terrific thermal equilibrium, remaining at 50 degrees Fahrenheit all year round. So for the ancestors it would need just a small fire to stay warm in winter, and naturally keep cool in the summer.

Just a portion of a building, its massive walls collapsed and now sealed above with concrete to prevent water damage, D-shaped Sun Temple is thought to have been an astronomical observatory. Alignment for solar and lunar matters suggest its builders understood both sun cycles and those of the moon. Another clue - there are no fragments from daily living - pot shards, basket fragments, food residue.

And at the base of its walls, some goldenrod and dainty lavender asters in bloom.

The first comers were hunter / gatherers. They hunted deer and rabbits, mountain goats and wild turkeys, and foraged for shoots and roots, nuts and berries. The basket maker cultures cooked their foods by baking, roasting, and parching. Water could be boiled, briefly, by dropping hot rocks into a container. Starting in the 6th century, the farmers living in central Mesa Verde were cultivating corn, beans, squash, and gourds. Corn and beans have complimentary amino acids and provide a complete protein but dry beans must briskly simmer for a long time, an hour or more, to cook. When pottery became "ordinary," beans became much easier to cook. This provided a high quality protein from a cultivated source, reducing reliance on hunting. Since beans are legumes with root nodules that fix atmospheric nitrogen, they also aided corn cultivation and would be likely to have increased the yield. With good conditions, 3 or 4 acres of land would provide enough food for a family of three or four individuals for one year, with supplementation from wild plants and hunting. Foraged plants might include seeds such as pinyon nuts and juniper berries, fruits such as rose hips and cactus fruits (prickly pear fruits provide a rare source of natural sugar) and greens such as goosefoot, pigweed, and purslane. Wild seeds were cooked and ground up into porridge.

Even in September, just driving along the road, I was able to find several wild foods that could be foraged. With more time and familiarity with the area it would be even easier.

Pinyon pine, Pinus edulis, has high caloric nuts rich in protein and fat. Delicious too. They need protection from insect damage in storage, which can be accomplished by parching, tossing the nuts in a basket with hot coals while constantly agitating to avoid burning the basket. Eat raw, shelled and roasted, grind and form into little cakes, mix with other seed to add richness and boil into a porridge, also mixed with pulp from yucca fruit and eaten as a pudding.

Utah juniper, Juniperus osteosperma (syn. J. utahensis), was used as a flavoring, added to soups and stews. Its medicinal qualities included the treatment of stomach aches, cough and headaches.

The fruit, called hips, of the wild rose, Rosa arizonica, is not important as a source of food. It is useful as a source of Vitamin C, and as a flavoring.

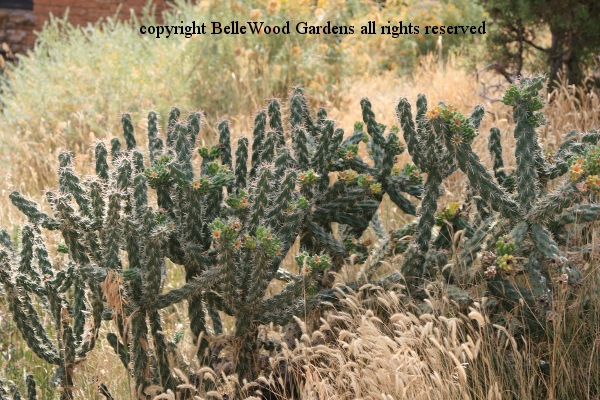

Cholla, also called staghorn or jumping cactus, Opuntia fulgida, has several seasons when it may be harvested. The big issue, of course, is removing the spines before cooking and eating. Low in caloric content but high in calcium, the flower buds are gathered in spring before they open, and the fruits when ripe in late summer. Even the joints themselves can be eaten, in times of scarcity. Baking would be a traditional, low water use, method of preparation.

Pricky pear, Opuntia phaeacantha (formerly O. Engelmannii) , is another cactus with options for consumption. The pads are called nopales. Smaller young ones in the spring are better than old, mature pads. They must have the sharp spines - especially numerous along the edges - removed. Cut however you like - diced or in thin strips - and then covered with water nopales will keep for a long time in the refrigerator, even for several weeks. Rinse before using.The red fruits are called tuna. Tuna need to be peeled to rid them of their spines, and also have the seeds scooped out. The seeds may be soaked in water, then strained, after which the liquid can be added to the mashed pulp and again strained.

In central Mexico the local recipe for a natural plaster is simple: clay, lime, borax and a slurry of cut-up nopal cactus paddles - five parts of water to one part of nopal. The lime acts as a stabilizer, borax retards molds and the gooey, slimey cactus works as a binder.

Yucca, Yucca baccata, hardly looks promising as a source of food. But - the large, fleshy fruits can be eaten raw or cooked, seeds ground into meal, tender inner leaves cooked in soup, and the roots pounded and soaked for a soap used to wash clothes and hair. Mature leaves are a source of fiber for cordage and making sandals.

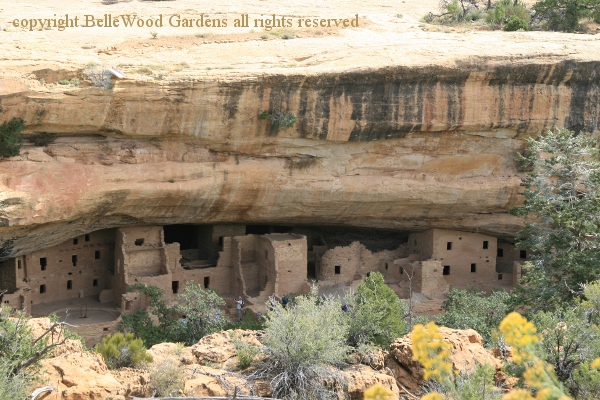

150 room Cliff Palace

A fascinating outing. For more information here's a link to a fascinating National Parks Service document from 1920 with wonderful descriptions and sketches of Mesa Verde cliff dwellings and structures.

Other entries are here, here and here

To Be Continued

Back to Top

Back to September 2015

Back to the main Diary Page